Edgar Allan Poe Tried and Failed to Crack the Mysterious Murder Case of Mary Rogers

After a teenage beauty turned up dead in the Hudson River, not even the godfather of detective fiction could figure out who done it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131031113141mary-rogers-murder-edgar-allan-poe.jpg)

She moved amid the bland perfume

That breathes of heaven’s balmiest isle;

Her eyes had starlight’s azure gloom

And a glimpse of heaven–her smile.

New York Herald, 1838

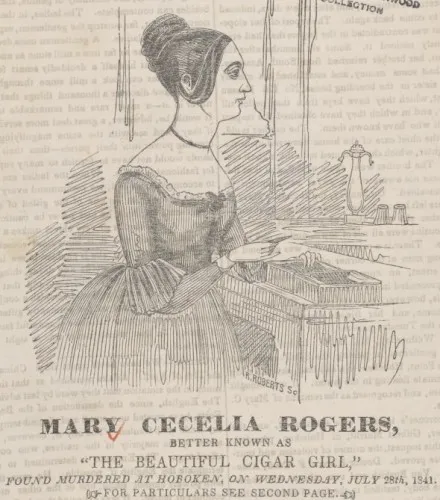

John Anderson’s Liberty Street cigar shop was no different from the dozens of other tobacco emporiums frequented by the newspapermen of New York City. There only reason it was so crowded was Mary Rogers.

Mary was the teenage daughter of a widowed boarding-house keeper, and her beauty was the stuff of legend. A poem dedicated to her visage appeared in the New York Herald, and during her time clerking at John Anderson’s shop she bestowed her heavenly smile upon writers like James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving, who would visit to smoke and flirt during breaks from their offices nearby.

In 1838, the cigar girl with ”the dainty figure and pretty face” went out and failed to return. Her mother discovered what appeared to be a suicide note; the New York Sun reported that the coroner had examined the letter and concluded the author had a “fixed and unalterable determination to destroy herself.” But a few days later Mary returned home, alive and well. She had been, it turned out, visiting a friend in Brooklyn. The Sun, which three years earlier had been responsible for the Great Moon Hoax, was accused of manufacturing Mary’s disappearance to sell newspapers. Her boss, John Anderson, was suspected of being in on the scheme, for after Mary returned his shop was busier than ever.

Still, the affair blew over, and Mary settled back into her role as an object of admiration for New York’s literary set. By 1841 she was engaged to Daniel Payne, a cork-cutter and boarder in her mother’s house. On Sunday, July 25, Mary announced plans to visit relatives in New Jersey and told Payne and her mother she’d be back the next day. The night Mary ventured out, a severe storm hit New York, and when Mary failed to return the next morning, her mother assumed she’d gotten caught in bad weather and delayed her trip home.

By Monday night, Mary still hadn’t come back, and her mother was concerned enough to place an advertisement in the following day’s Sun asking for anyone who might have seen Mary to have the girl contact her, as “it is supposed some accident has befallen her.” Foul play was not suspected.

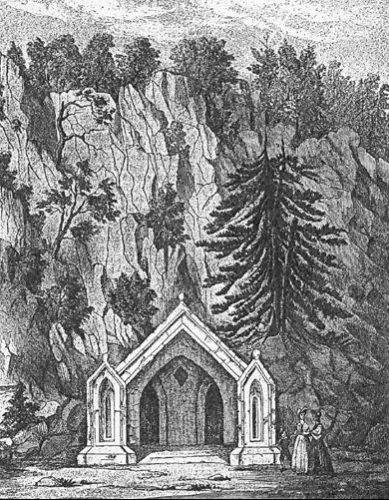

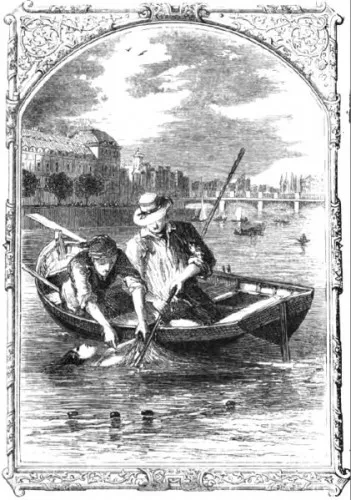

On July 28, some men were out for a stroll near Sybil’s Cave, a bucolic Hudson riverside spot in Hoboken, New Jersey, when a bobbing figure caught their attention. Rowing out in a small boat, they dragged what turned out to be the body of a young woman back to shore. Crowds gathered, and within hours, a former fiancee of Mary’s identified the body as hers.

According to the coroner, her dress and hat were torn and her body looked as though it had taken a beating. She was also, the coroner took care to note, not pregnant, and “had evidently been a person of chastity and correct habits.”

Questions abounded: Had Mary been killed by someone she knew? Had she been a victim of a random crime of opportunity, something New Yorkers increasingly worried about as the city grew and young women strayed farther and farther from the family parlor? Why hadn’t the police of New York or Hoboken spotted Mary and her attacker? The Herald, the Sun and the Tribune all put Mary on their front pages, and no detail was too lurid—graphic descriptions of Mary’s body appeared in each paper, along with vivid theories about what her killer or killers might have done to her. More than anything, they demanded answers.

Suspicion fell immediately upon Daniel Payne, Mary’s fiancee; perhaps one or the other had threatened to leave, and Payne killed her, either to get rid of her or to prevent her from breaking their engagement. He produced an airtight alibi for his whereabouts during Mary’s disappearance, but that didn’t stop the New-Yorker (a publication unrelated to the current magazine of that name) from suggesting, in August of 1841, that he’d had a hand in Mary’s death:

There is one point in Mr. Payne’s testimony which is worthy of remark. It seems he had been searching for Miss Rogers—his betrothed—two or three days; yet when he was informed on Wednesday evening that her body had been found at Hoboken, he did not go to see it or inquire into the matter—in fact, it appears that he never went at all, though he had been there inquiring for her before. This is odd, and should be explained.

If Payne hadn’t killed Mary, it was theorized, she’d been caught by a gang of criminals. This idea was given further credence later that August, when two Hoboken boys who were out in the woods collecting sassafras for their mother, tavern owner Frederica Loss, happened upon several items of women’s clothing. The Herald reported that “the clothes had all evidently been there at least three or four weeks. They were all mildewed down hard…the grass had grown around and over some of them. The scarf and the petticoat were crumpled up as if in a struggle.” The most suggestive item was a handkerchief embroidered with the initials M.R.

The discovery of the clothes catapulted Loss into minor celebrity. She spoke with reporters at length about Mary, whom she claimed to have seen in the company of a tall, dark stranger on the evening of July 25. The two had ordered lemonade and then taken their leave from Loss’ tavern. Later that night, she said, she heard a scream coming from the woods. At the time, she’d thought it was one of her sons, but after going out to investigate and finding her boy safely inside, she’d decided it must have been an animal. In light of the clothing discovery so close to her tavern, though, she now felt certain it had come from Mary.

The Herald and other papers took this as evidence that strangers had indeed absconded with Mary, but despite weeks of breathless speculation, no further clues were found and no suspects identified. The city moved on, and Mary’s story became yesterday’s news—only to return to the headlines.

In October 1841, Daniel Payne went on a drinking binge that carried him to Hoboken. After spending October 7 going from tavern to tavern to tavern, he entered a pharmacy and bought a vial of laudanum. He stumbled down to where Mary’s body had been brought to shore, collapsed onto a bench, and died, leaving behind a note: “To the World—Here I am on the very spot. May God forgive me for my misspent life.” The consensus was that his heart had been broken.

While the newspapers had their way with Mary’s life and death, Edgar Allen Poe turned to fact-based fiction to make sense of the case.

Working in the spring of 1842, Edgar Allan Poe transported Mary’s tale to Paris and, in “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” gave her a slightly more Francophone name (and a job in a perfume shop), but the details otherwise match exactly. The opening of Poe’s story makes his intent clear:

The extraordinary details which I am now called upon to make public, will be found to form, as regards sequence of time, the primary branch of a series of scarcely intelligible coincidences, whose secondary or concluding branch will be recognized by all readers in the late murder of MARY CECILIA ROGERS, at New York.

A sequel to “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” widely considered the first detective story ever set to print, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” would see the detective Dupin solve the young woman’s murder. In shopping the story to editors, Poe suggested he’d gone beyond mere storytelling: “Under the pretense of showing how Dupin unraveled the mystery of Marie’s assassination, I, in fact, enter into a very rigorous analysis of the real tragedy in New York.”

Though he appropriated the details of Mary’s story, Poe still faced the very real challenge of actually solving the murder when the police were no closer than they’d been in July 1841.

Like many other stories of the mid-19th century, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” was serialized, appearing in November issues of Snowden’s Ladies Companion. The third part, in which Dupin put together the details of the crime but left the identity of the criminal up in the air, was to appear at the end of the month, but a shocking piece of news delayed the final installment.

In October 1842, Frederica Loss was accidentally shot by one of her sons and made a deathbed confession regarding Mary Rogers. The “tall, dark” man she’d seen the girl with in July 1841 had not been a stranger; she knew him. The Tribune reported: “On the Sunday of Miss Rogers’s disappearance she came to her house from this city in company with a young physician, who undertook to produce for her a premature delivery.” (“Premature delivery” being a euphemism for abortion.)

The procedure had gone wrong, Loss said, and Mary had died. After disposing of her body in the river, one of Loss’ sons had thrown her clothes in a neighbor’s pond and then, after having second thoughts, scattered them in the woods.

While Loss’ confession did not entirely match the evidence (there was still the matter of Mary’s body, which bore signs of some kind of struggle), the Tribune seemed satisfied: “Thus has this fearful mystery, which has struck fear and terror to so many hearts, been at last explained by circumstances in which no one can fail to perceive a Providential agency.”

To some, the attribution of Mary’s death to a botched abortion made perfect sense—it had been suggested that she and Payne quarreled over an unwanted pregnancy, and in the early 1840s New York City was fervently debating the activities of the abortionist Madame Restell. Several penny presses had linked Rogers to Restell (and suggested that her 1838 disappearance lasted precisely as long as it would take a woman to terminate a pregnancy in secret and return undiscovered), and while that connection was ultimately unsubstantiated, Mary was on the minds of New Yorkers when, in 1845, they officially criminalized the procedure.

Poe’s story was considered a sorry follow up to “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” but he did manage to work Loss’ story into his narrative. His Marie Rogêt had indeed kept company with a “swarthy naval officer” who may very well have killed her, though by what means we are not sure—did he murder her outright or lead her into a “fatal accident,” a plan of “concealment”?

Officially, the death of Mary Rogers remains unsolved. Poe’s account remains the most widely read, and his hints at abortion (made even clearer in an 1845 reprinting of the story, though the word “abortion” never appears) have, for most, closed the case. Still, those looking for Poe to put the Mary Rogers case to rest are left to their own devices. In a letter to a friend, Poe wrote: “Nothing was omitted in Marie Rogêt but what I omitted myself—all that is mystification.”

Sources:

Poe, Edgar Allan, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt”; “The Mary Rogers Mystery Explained”, New-York Daily Tribune, Nov. 18, 1842; “The Case of Mary C. Rogers”, The New-Yorker; Aug. 14, 1841; Stashower, Daniel, The Beautiful Cigar Girl (PenguinBooks, 2006); Srebnick, Amy Gilman, The Mysterious Death of Mary Rogers: Sex and Culture in Nineteenth Century New York (Oxford University Press, 1995); Meyers, Jeffrey, Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Cooper Square Press, 1992)